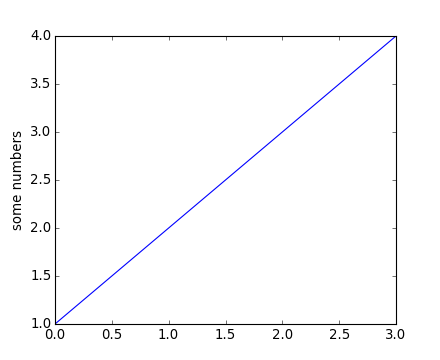

matplotlib.pyplot is a collection of command style functions that make matplotlib work like MATLAB. Each pyplot function makes some change to a figure: e.g., create a figure, create a plotting area in a figure, plot some lines in a plotting area, decorate the plot with labels, etc.... matplotlib.pyplot is stateful, in that it keeps track of the current figure and plotting area, and the plotting functions are directed to the current axes

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot([1,2,3,4])

plt.ylabel('some numbers')

plt.show()

(Source code, png)

You may be wondering why the x-axis ranges from 0-3 and the y-axis from 1-4. If you provide a single list or array to the plot() command, matplotlib assumes it is a sequence of y values, and automatically generates the x values for you. Since python ranges start with 0, the default x vector has the same length as y but starts with 0. Hence the x data are [0,1,2,3].

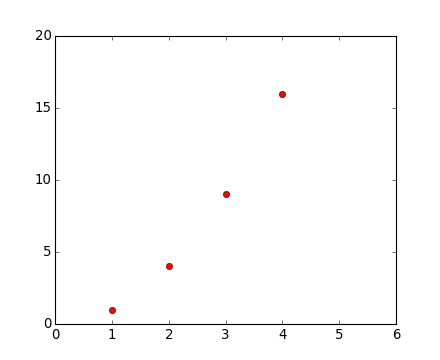

plot() is a versatile command, and will take an arbitrary number of arguments. For example, to plot x versus y, you can issue the command:

plt.plot([1,2,3,4], [1,4,9,16])

For every x, y pair of arguments, there is an optional third argument which is the format string that indicates the color and line type of the plot. The letters and symbols of the format string are from MATLAB, and you concatenate a color string with a line style string. The default format string is ‘b-‘, which is a solid blue line. For example, to plot the above with red circles, you would issue

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot([1,2,3,4], [1,4,9,16], 'ro')

plt.axis([0, 6, 0, 20])

plt.show()

(Source code, png)

See the plot() documentation for a complete list of line styles and format strings. The axis() command in the example above takes a list of [xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax] and specifies the viewport of the axes.

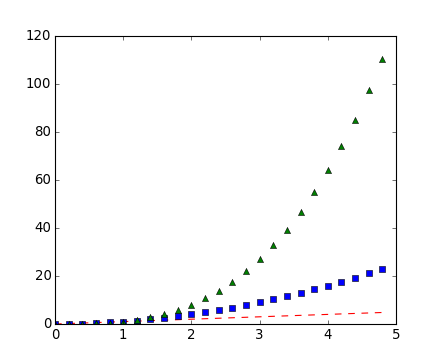

If matplotlib were limited to working with lists, it would be fairly useless for numeric processing. Generally, you will use numpy arrays. In fact, all sequences are converted to numpy arrays internally. The example below illustrates a plotting several lines with different format styles in one command using arrays.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# evenly sampled time at 200ms intervals

t = np.arange(0., 5., 0.2)

# red dashes, blue squares and green triangles

plt.plot(t, t, 'r--', t, t**2, 'bs', t, t**3, 'g^')

plt.show()

(Source code, png)

Lines have many attributes that you can set: linewidth, dash style, antialiased, etc; see matplotlib.lines.Line2D. There are several ways to set line properties

Use keyword args:

plt.plot(x, y, linewidth=2.0)

Use the setter methods of the Line2D instance. plot returns a list of lines; e.g., line1, line2 = plot(x1,y1,x2,y2). Below I have only one line so it is a list of length 1. I use tuple unpacking in the line, = plot(x, y, 'o') to get the first element of the list:

line, = plt.plot(x, y, '-')

line.set_antialiased(False) # turn off antialising

Use the setp() command. The example below uses a MATLAB-style command to set multiple properties on a list of lines. setp works transparently with a list of objects or a single object. You can either use python keyword arguments or MATLAB-style string/value pairs:

lines = plt.plot(x1, y1, x2, y2)

# use keyword args

plt.setp(lines, color='r', linewidth=2.0)

# or MATLAB style string value pairs

plt.setp(lines, 'color', 'r', 'linewidth', 2.0)

Here are the available Line2D properties.

| Property | Value Type |

|---|---|

| alpha | float |

| animated | [True | False] |

| antialiased or aa | [True | False] |

| clip_box | a matplotlib.transform.Bbox instance |

| clip_on | [True | False] |

| clip_path | a Path instance and a Transform instance, a Patch |

| color or c | any matplotlib color |

| contains | the hit testing function |

| dash_capstyle | ['butt' | 'round' | 'projecting'] |

| dash_joinstyle | ['miter' | 'round' | 'bevel'] |

| dashes | sequence of on/off ink in points |

| data | (np.array xdata, np.array ydata) |

| figure | a matplotlib.figure.Figure instance |

| label | any string |

| linestyle or ls | [ '-' | '--' | '-.' | ':' | 'steps' | ...] |

| linewidth or lw | float value in points |

| lod | [True | False] |

| marker | [ '+' | ',' | '.' | '1' | '2' | '3' | '4' ] |

| markeredgecolor or mec | any matplotlib color |

| markeredgewidth or mew | float value in points |

| markerfacecolor or mfc | any matplotlib color |

| markersize or ms | float |

| markevery | [ None | integer | (startind, stride) ] |

| picker | used in interactive line selection |

| pickradius | the line pick selection radius |

| solid_capstyle | ['butt' | 'round' | 'projecting'] |

| solid_joinstyle | ['miter' | 'round' | 'bevel'] |

| transform | a matplotlib.transforms.Transform instance |

| visible | [True | False] |

| xdata | np.array |

| ydata | np.array |

| zorder | any number |

To get a list of settable line properties, call the setp() function with a line or lines as argument

In [69]: lines = plt.plot([1,2,3])

In [70]: plt.setp(lines)

alpha: float

animated: [True | False]

antialiased or aa: [True | False]

...snip

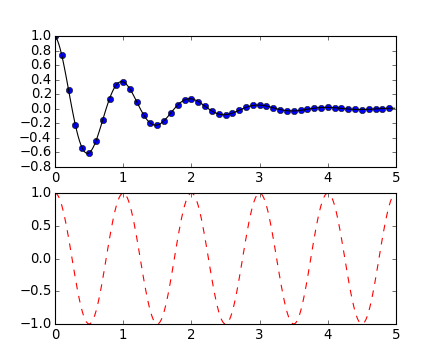

MATLAB, and pyplot, have the concept of the current figure and the current axes. All plotting commands apply to the current axes. The function gca() returns the current axes (a matplotlib.axes.Axes instance), and gcf() returns the current figure (matplotlib.figure.Figure instance). Normally, you don’t have to worry about this, because it is all taken care of behind the scenes. Below is a script to create two subplots.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

def f(t):

return np.exp(-t) * np.cos(2*np.pi*t)

t1 = np.arange(0.0, 5.0, 0.1)

t2 = np.arange(0.0, 5.0, 0.02)

plt.figure(1)

plt.subplot(211)

plt.plot(t1, f(t1), 'bo', t2, f(t2), 'k')

plt.subplot(212)

plt.plot(t2, np.cos(2*np.pi*t2), 'r--')

plt.show()

(Source code, png)

The figure() command here is optional because figure(1) will be created by default, just as a subplot(111) will be created by default if you don’t manually specify an axes. The subplot() command specifies numrows, numcols, fignum where fignum ranges from 1 to numrows*numcols. The commas in the subplot command are optional if numrows*numcols<10. So subplot(211) is identical to subplot(2,1,1). You can create an arbitrary number of subplots and axes. If you want to place an axes manually, i.e., not on a rectangular grid, use the axes() command, which allows you to specify the location as axes([left, bottom, width, height]) where all values are in fractional (0 to 1) coordinates. See pylab_examples example code: axes_demo.py for an example of placing axes manually and pylab_examples example code: subplots_demo.py for an example with lots-o-subplots.

You can create multiple figures by using multiple figure() calls with an increasing figure number. Of course, each figure can contain as many axes and subplots as your heart desires:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(1) # the first figure

plt.subplot(211) # the first subplot in the first figure

plt.plot([1,2,3])

plt.subplot(212) # the second subplot in the first figure

plt.plot([4,5,6])

plt.figure(2) # a second figure

plt.plot([4,5,6]) # creates a subplot(111) by default

plt.figure(1) # figure 1 current; subplot(212) still current

plt.subplot(211) # make subplot(211) in figure1 current

plt.title('Easy as 1,2,3') # subplot 211 title

You can clear the current figure with clf() and the current axes with cla(). If you find this statefulness, annoying, don’t despair, this is just a thin stateful wrapper around an object oriented API, which you can use instead (see Artist tutorial)

If you are making a long sequence of figures, you need to be aware of one more thing: the memory required for a figure is not completely released until the figure is explicitly closed with close(). Deleting all references to the figure, and/or using the window manager to kill the window in which the figure appears on the screen, is not enough, because pyplot maintains internal references until close() is called.

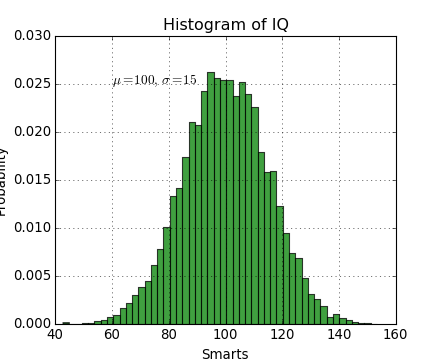

The text() command can be used to add text in an arbitrary location, and the xlabel(), ylabel() and title() are used to add text in the indicated locations (see Text introduction for a more detailed example)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

mu, sigma = 100, 15

x = mu + sigma * np.random.randn(10000)

# the histogram of the data

n, bins, patches = plt.hist(x, 50, normed=1, facecolor='g', alpha=0.75)

plt.xlabel('Smarts')

plt.ylabel('Probability')

plt.title('Histogram of IQ')

plt.text(60, .025, r'$\mu=100,\ \sigma=15$')

plt.axis([40, 160, 0, 0.03])

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

(Source code, png)

All of the text() commands return an matplotlib.text.Text instance. Just as with with lines above, you can customize the properties by passing keyword arguments into the text functions or using setp():

t = plt.xlabel('my data', fontsize=14, color='red')

These properties are covered in more detail in Text properties and layout.

matplotlib accepts TeX equation expressions in any text expression.

For example to write the expression  in the title,

you can write a TeX expression surrounded by dollar signs:

in the title,

you can write a TeX expression surrounded by dollar signs:

plt.title(r'$\sigma_i=15$')

The r preceding the title string is important – it signifies that the string is a raw string and not to treat backslashes as python escapes. matplotlib has a built-in TeX expression parser and layout engine, and ships its own math fonts – for details see Writing mathematical expressions. Thus you can use mathematical text across platforms without requiring a TeX installation. For those who have LaTeX and dvipng installed, you can also use LaTeX to format your text and incorporate the output directly into your display figures or saved postscript – see Text rendering With LaTeX.

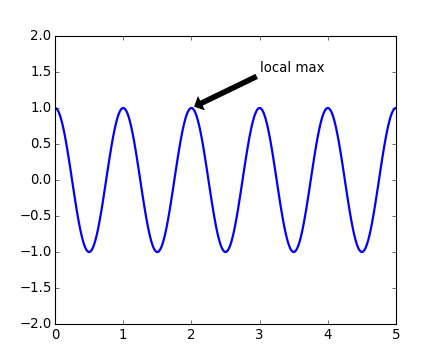

The uses of the basic text() command above place text at an arbitrary position on the Axes. A common use case of text is to annotate some feature of the plot, and the annotate() method provides helper functionality to make annotations easy. In an annotation, there are two points to consider: the location being annotated represented by the argument xy and the location of the text xytext. Both of these arguments are (x,y) tuples.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ax = plt.subplot(111)

t = np.arange(0.0, 5.0, 0.01)

s = np.cos(2*np.pi*t)

line, = plt.plot(t, s, lw=2)

plt.annotate('local max', xy=(2, 1), xytext=(3, 1.5),

arrowprops=dict(facecolor='black', shrink=0.05),

)

plt.ylim(-2,2)

plt.show()

(Source code, png)

In this basic example, both the xy (arrow tip) and xytext locations (text location) are in data coordinates. There are a variety of other coordinate systems one can choose – see Annotating text and Annotating Axes for details. More examples can be found in pylab_examples example code: annotation_demo.py.